Explore the role and design of mosaics from across Roman Britain

Mosaics have been found across the Roman Empire, including in Britain. They were commonly used to adorn the floors of the private villas of wealthy citizens, as well as public buildings including bathhouses.

They were made by combining small, coloured stones or tiles called tesserae, usually sourced from local materials.

Time-consuming to produce, they allowing people to showcase their wealth and status.

Exploring Roman mosaics today

Today, a range of mosaics give us information about cultural influences of the time as well as changing tastes. You can explore a range of them on this site, or investigate a site near you.

However, it’s also worth remembering that so much evidence of Roman Britain remains hidden beneath the surface of the land – including ornate and decorative mosaics that may never be uncovered.

Watch the Video for an introduction to Roman mosaics, based on a fragment from an example from Beadlam Roman Villa (English Heritage) in North Yorkshire.

Watch The Video With Subtitles

The Romans across Britain

You may be surprised by the number of Romano-British mosaics that have been found. This evidence of Roman occupation helps us understand aspects of the era when Britain was part of a vast empire stretching from the Mediterranean up through to the north of England and briefly into southern Scotland.

Roman mosaics from Roman Corinium

Corinium Museum, Cirencester

Cirencester has one of the best collections of Roman mosaics ever found in Britain. More than 90 mosaic pavements have been discovered in the area that was once Roman Corinium, making it an excellent place to explore Roman life through these colourful artworks.

Cirencester, known by the Romans as Corinium, was one of the most important towns in Roman Britain. It was originally built as a fort in the 1st century AD but also became a busy centre for trade and local government. Corinium quickly grew into a thriving town, becoming second only to London in importance and size.

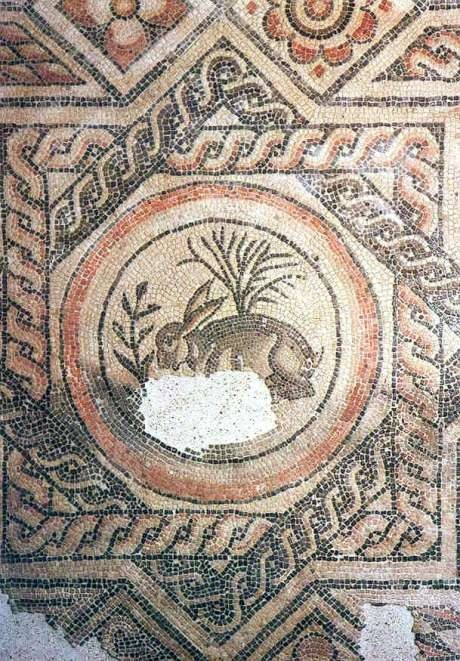

This very special mosaic, dating from the 4th century AD, was found in excavations at Beeches Road, Cirencester in 1971.

As well as the complex geometrical features, it also has a very accomplished animal design, for example using clear glass tesserae to highlight the fur on the creature’s back. Hares feature occasionally in other mosaic designs, mostly in hunting scenes. The Beeches Road hare is unique in showing the animal feeding.

Roman mosaic hunting designs explained

Hunting scenes commonly appeared in Roman mosaics, often in wealthy Roman houses and villas. These scenes symbolised wealth, power, and skill, since hunting was considered an elite activity. They also had a storytelling function too, sometimes sharing mythological themes and showing gods or legendary heroes. Hunting scenes were visually appealing and must have made great pieces for entertaining guests.

This ‘hunting design’ mosaic was discovered beneath Dyer Street in Cirencester in 1849 and led directly to the creation of the town’s first Corinium Museum.

At the centre of the mosaic, there are three dogs shown hunting together, with the largest dog clearly wearing a collar. Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly what animal they were chasing, as this section of the mosaic was damaged when it was found and has since been filled in using simple tiles.

Roman Mosaics in present-day Yorkshire

‘Helicon’ mosaic, from Aldborough Roman Site, North Yorkshire, English Heritage

The Romans invaded Britain in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius and made it part of the Roman Empire. They made advances into the northern regions from around AD 70. They built roads, towns, and Hadrian’s Wall to protect the northern border.

Aldborough was the prosperous Roman town of Isurium Brigantum. From around AD 120 to AD 400, it was the the civilian ‘capital’ of an extensive region of north Britain, strategically important as it was on a road network and on the river Ure.

This mosaic dates from around AD 300 and was found in 1846. Originally part of the floor in a Roman dining room, this section shows the lower half of a female figure dressed in a tunic, holding a mask and a scroll. Experts think she represents either Melpomene (the Muse of Tragedy) or Thalia (the Muse of Comedy). Below her left elbow, the word ‘Helikon’ is written in rare blue glass tiles using Greek letters. The original mosaic probably featured nine figures along with a picture of Mount Helicon.

Fragment showing geometric design

From Beadlam Roman Villa, North Yorkshire, English Heritage

This Roman villa was hidden away in a field near the North Yorkshire village of Beadlam, on the edge of the North York Moors, up until the middle of the 20th century. The villa at Beadlam, on the bank of a small river, was excavated during the 1960s and 70s, revealing a range of domestic objects.

It was a typical Romano-British villa, designed as a winged-corridor house with communal rooms at its centre and two private suites of well-furnished rooms on either side.

The west wing included a room equipped with a hypocaust heating system, while it was in the east wing in an ornate reception room that the mosaic was found. Watch the video (above) to find out more about this fascinating object.

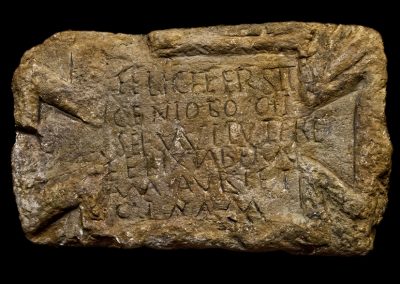

Fragments of mosaic from the Kirk Sink Roman Villa, Gargrave

From Craven Museum and Gallery

The Kirk Sink Roman villa near Skipton was discovered in the late 18th century and is one of North Yorkshire’s important Roman sites.

Excavations revealed a substantial villa complex that included rooms decorated with mosaics, bathhouses, and evidence of farming and daily life. Archaeologists also uncovered pottery, coins, and personal items, suggesting it was occupied by wealthy Romans or Romano-British inhabitants. Although much of the site is no longer visible today, Kirk Sink villa provides valuable insights into rural life in Roman Britain.

Explore mosaic designs

A wide range of mosaics have been found. Explore a selection here.

Colours and Design

What colours can you see in the mosaics? Why do you think so many mosaics share similar colours?

What different shapes can you spot in the designs? Why do you think some shapes were popular?

What other similarities can you spot between the mosaics?

Which is your favourite design?

If you could see the whole mosaic, what do you think the rest of it would look like?

Materials and Techniques

How do you think the mosaics were made?

What materials were used?

Does it surprise you that some Roman mosaic designs have mistakes in them?

Historical Context and Meaning

Why do you think the Romans decorated their floors with mosaics instead of using plain stone or wood?

What do the mosaics tell us about the wealth and status of the people who owned them?

How does a Roman mosaic compare to modern flooring and decoration?

Archaeology

How do you think the mosaics or fragments survived for so long?

What challenges do archaeologists face when trying to preserve ancient mosaics?

Short drama activities

These are great ways to generate ideas quickly and don’t need to take very long. When you’re first trying out hot-seating activities, it can work well for the group leader or teacher to be the one in role, with the group asking questions.

Hotseat a member of the class in role as the craftsman who created one of the mosaics. Is he happy with his design? Was it hard work to create? What were the challenges?

Interview a member of the class in role the archaeologist who found the hunting mosaic from Corinium Museum. What do they think is going on in the mosaic? How do they feel about the missing section?

Role-play

Sometimes, individual tesserae or small fragments of mosaics can be found. In pairs, imagine finding some tesserae.

What would you think they were? One person could correctly identify them and try and convince their disbelieving friend. What would you say to persuade them?

Create your own

Design your own mosaic using small squares of paper to represent the tesserae.

What design would you choose to put on yours? For more complex designs, you might need to try sketching an outline in pencil first.

Vocabulary

Mosaic: A decorative artwork created by arranging small pieces of coloured stone, glass, or ceramic

Tesserae: The small tiles or cubes used to make mosaics

Villa: A large Roman country house, usually belonging to wealthy families

Romano-British: Referring to the period and culture when Britain was part of the Roman Empire

Excavation: The careful digging and recording of archaeological sites

Mortar: A type of cement used by Romans to fix tesserae in place

Mount Helicon: A mountain in Greece linked to creativity and the Muses in Roman and Greek mythology

There are lots of ways to explore Roman archaeological remains across the country – if you live in England or Wales, there’ll probably be a site nearer than you think (although it may not have been uncovered yet).

If you’ve been inspired to find out more about the role of archaeologists, there are lots of ways to get involved in community digs. In nearby Scarborough, the Scarborough Archaeological and Historical Society runs regular excavations and open days. Organisations including DigVentures to organise community digs and run events in lots of places – perhaps there’s one near you.

You can also find out more about becoming a Young Archaeologist or visit the website of the Council for British Archaeology.

English Heritage has been working together with the Ryevitalise Landscape Partnership to connect people with the historic landscape, including supporting with the tours that take place at Beadlam Roman Villa (pre-arranged visits only).

Schools can also book a free self-led visit to Aldborough Roman Site (English Heritage).

The Corinium Museum in Cirencester has one of the best collections of mosaics, with a large number of designs to explore.