Enter the World of Global Maritime Navigation

At Kiplin Hall and Gardens

These curious instruments belonged to John Delaval Carpenter (1790 – 1853), the 4th Earl of Tyrconnel, a title he inherited from his uncle. Carpenter was a British peer and member of the North York Corps of Yeomanry. He lived at Kiplin Hall, using these implements on his yacht. However, upon his death, they were inherited by a Royal Navy captain. At least one of these objects travelled the world to British colonies in the Caribbean.

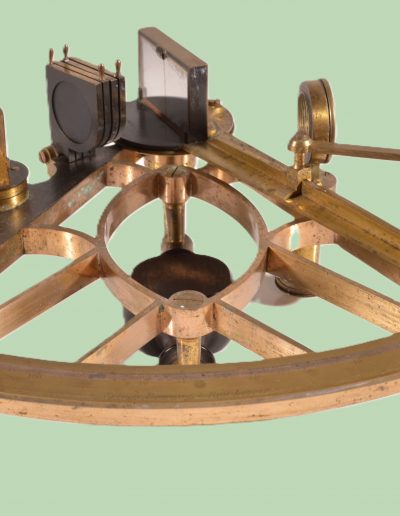

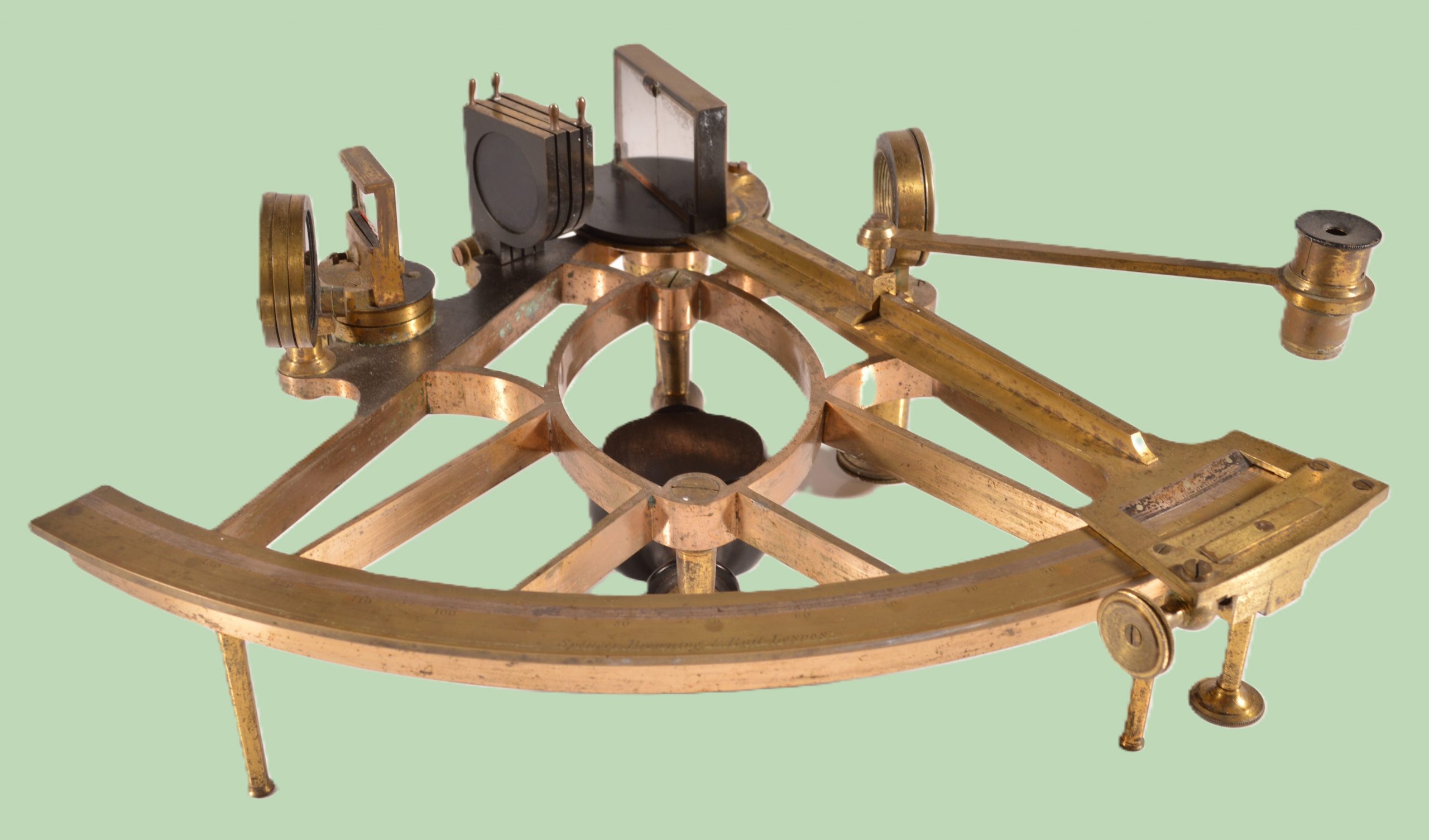

A Sextant

This object was designed for used by sailors to work out where they were out at sea. If you know where you are, you can work out how to get to your destination!

Before the invention of modern navigation equipment, sailing ships needed to know two things to work out their position- how far north/south they are and how far west/east they were. This information provides the coordinates for their position on the Earth. Kiplin Hall and Gardens, where the sextant is kept, has the coordinates 54o22’19.32”N 1o34’44.36”W.

The north/south position is called latitude and can be worked out using the sextant. If you look carefully at the object you can see it has mirrors and pieces of glass in the top part. The bottom part is curved and has a number scale on it. It is used to measure the angle between the sun and the horizon.

At midday the sun is at its highest in the sky. The further you are away from the equator the lower the sun will be compared to the horizon. If you know how high the sun is at midday you can work out how far north you are. The sextant does this by lining up two images, the horizon and the sun, when you look through the telescope part. When you adjust the sextant to make the images line up, you can read the angle of the sun in the sky from the curved scale.

The problem is if you only know how far north you are, you could be anywhere east to west. York has the same latitude as Edmonton in Canada. To work out your west/east you need to know the time… you need a marine chronometer.

Watch the Video – to explore this object with your group

Watch The Video With Subtitles

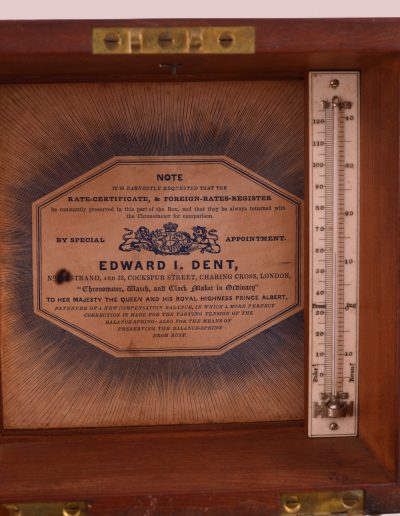

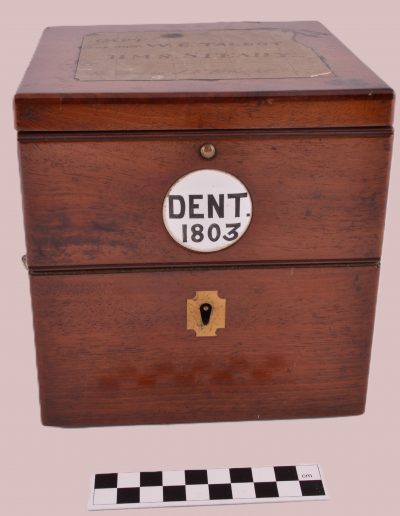

A Marine Chronometer

A marine chronometer is a clock that works on a ship. This chronometer came from the company Dent, in London, which has a royal warrant and had supplied the royal family.

If you look carefully at the object you can see that the clock is mounted on some metal rings called a gimbal. This allows the clock to stay steady even in rough seas so that it can work smoothly and keep good time.

Greenwich was chosen as the site for a Royal Observatory in 1674. It became the point where all west/east points were measured. We call the east/west position longitude.

When ships sail around the Earth, the sun rises and sets at different times from those at home. This is because the Earth is spinning which makes the sun seem to rise and set. The times of rising and setting depend on where you are on the globe.

If you know what the time is in Greenwich, London, you can compare the position of the sun in the sky where you are, to where it would be in the sky if you were in Greenwich. For example if midday was 12 hours later in your position than in Greenwich, you would be exactly on the other side of the world!

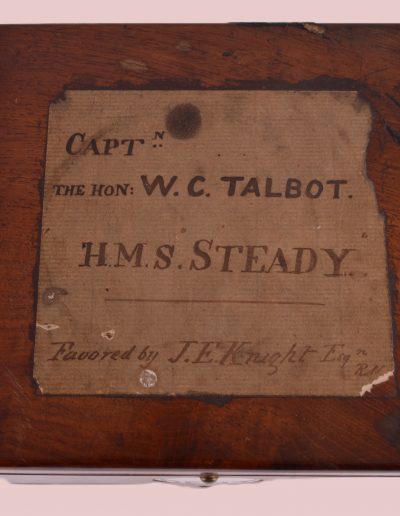

Sailors needed a really accurate clock that didn’t lose or gain time. The marine chronometer was designed to do that. If it went wrong, the captain wouldn’t know the time in Greenwich and so wouldn’t be able to work out his longitude – he would be lost. This chronometer is engraved with name Captain W.C. Talbot and the name of the Royal Navy ship, H.M.S Steady. But the story doesn’t end there…

Who used this chronometer?

Captain Walter Talbot seems to have inherited these objects, after his cousin John Carpenter had died. Talbot inherited Kiplin Hall from John, living there from 1887 until 1904, and also took the name Carpenter.

Talbot clearly intended to use the chronometer in his role as the captain of HMS Steady from 1864. However, after Talbot had set sail from Southampton, the captain of the larger HMS Fawn died and Talbot was given that more prestigious position instead. He was based in the Caribbean Sea, in Jamaica, Bahamas, Cuba and Belize, visiting Nassau, Port Royal, Cochrane Anchorage, Havana and Belize, as part of British colonial policy.

Why was Talbot based in the Caribbean?

Half a century earlier, British men in the Caribbean were likely to have been there because of involvement in the slave trade. However, by Talbot’s time, the Royal Navy had a role to play in anti-slavery patrols. Britain had abolished slavery in its empire in 1833. Men like Talbot were involved in enforcing the ban on the transatlantic slave trade whilst simultaneously protecting British colonial interests and trade routes. The Caribbean remained an important region for sugar and other products. Even today, many Caribbean countries are still part of the Commonwealth.

Activity – introduce this object as a mystery

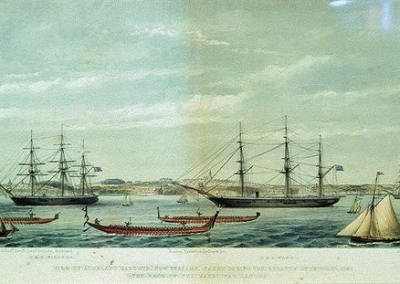

Explore HMS Fawn

What did Captain Walter Talbot’s ship look like? We don’t have an image of HMS Fawn from 1864 when Talbot was captain and when the marine chronometer was very likely used, but we do have some paintings from slightly earlier that decade and a few years later.

Firstly, from 1862 you can see HMS Fawn and HMS Miranda taking part in a regatta, by F R Slack (artist) and Day and Son (engravers), from the National Maritime Museum collection.

In 1880, HMS Fawn was also shown caught in a squall by artist Richard Brydges Beechey, painted in oil on canvas. Beechey joined the Royal Navy aged 14 and, like other members of his family, became a celebrated painter, specialising in naval scenes and painting ports. This painting of HMS Fawn was one of a series of paintings representing actions and commands of its captain, the future Admiral Ralph Peter Cator (1829–1903).

Talking Points

Sextant

Light travels in straight lines. Can you trace the path of a light ray through the sextant to the telescope?

What was the job of the mirrors?

Looking at the sun is never a good idea. It can cause blindness. How do you think the 3 pieces of glass at the front of the sextant helped to stop eye damage?

The sextant is made from brass or bronze. Why do you think these metal alloys are better than iron for something we use at sea?

Sailors didn’t just need to know their latitude in the day. How do you think they could navigate at night?

During the winter the sun doesn’t go as high in the sky compared to summer. Can you explain why? How might this affect the accuracy of the sextant?

A bit more difficult…one of the mirrors in the sextant is described as half-silvered. How do you think this helps to focus the image of the two objects into the same eyepiece?

Marine Chronometer

The marine chronometer is in a very strong wooden box. What other protection would you add to make sure that this valuable object was safe at sea?

This clock was run by clockwork. It has to be wound up every two days to keep working. Are there any clues on the box to show how this was done?

Where is the energy stored in a wind up clock?

Can you see the thermometer attached to the lid of the clock. Why might this be useful on a sailing ship?

The clock face has a dial to show the state of winds. Why might this be useful to a sailing ship?

Today we use GPS to find our position. What do you think would happen if someone turned off all the satellites? How would we navigate around the world?

What does the engraving on the lid suggest about this object? What sorts of objects do we get engraved? Do you think Captain Talbot minded that it was engraved with the name of the wrong ship?

Vocabulary

Latitude: how far north/south you are compared to the equator

Longitude: how far west/east you are from Greenwich, London

Navigation: finding your way from one place to another

Coordinates: usually 2 numbers that give your position on a map

Gimbal: a device to keep an object level

In the Classroom

Try it yourself

Use your watch to find your way.

If you have a watch with hands you can use it to find which way is south. Hold the watch flat and point the hour hand towards the sun – but don’t look directly at the sun.

Find the hour mark on the watch that is halfway between the hour hand and the 12. This halfway mark is pointing south.

Museum Location

Find out more about the history of transport and travel

Explore more objects with links to colonialism