Waterwheel from the Providence Mine, Kettlewell

Dales Countryside Museum

Kettlewell in the Yorkshire Dales is built on rocks that are rich in minerals. These minerals have been mined for centuries and the products sold for profit.

Until 1875, there was a lot of mining for a lead ore called ‘galena’, used for making waterpipes and for waterproofing roofs, amongst many other things. Galena is rich is lead, making extracting it easier. However, when the rocks were dug out of the ground in large pieces, they also contained other stone. The large rocks therefore needed to be crushed before the galena could be separated and sent for smelting.

Smelting involves heating the lead to a high temperature until the metal melts and can be collected, leaving the impurities behind.

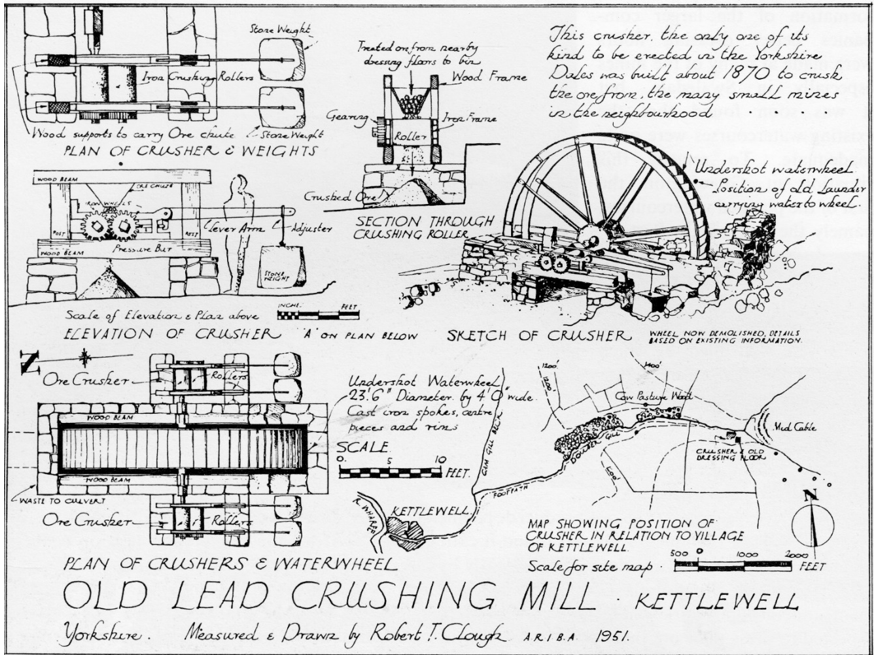

At Providence Mine in Kettlewell, a large waterwheel was made with double crushing rollers to allow more rocks to be processed more quickly for the valuable lead ore. It measures 6.4 metres in diameter and is more than a metre wide. Made from iron, wood and stone, it was restored by volunteers and can now be seen at the Dales Countryside Museum in Hawes.

How does a waterwheel work?

Waterwheels like this one from the Providence Mine had buckets around the rim. These collected water from a running stream of water, known as a ‘leat’.

The centre of the large wheel sat on an axle. As the wheel was turned by the flowing water, the axle turned a metal gear which was attached to a cylindrical grinding stone. This gear connected to a second gear which in turn rotated another grinding stone, this time in the opposite direction.

In a waterwheel like this, the two grinding stones were located close together so that rocks could be poured into the gap to be crushed. It worked like an old fashioned clothes mangle, though much more powerful.

In this way, the waterwheel used potential energy in the water coming downhill to turn the wheel as the buckets filled. This potential energy was converted into kinetic energy. The kinetic energy provided the power to crush the stones.

Clever engineering

A waterwheel is able to take a small amount of force from lots water, concentrating it into a large force to crush a smaller amount of rock.

The turning force is produced close to the axle by the water that is more distant. It acts like a massive circular lever. If you think about opening a tin of paint, it is really difficult if you try to take the lid off with your fingernails, but much easier if you use a screwdriver to multiply your force to lever the lid off.

What were conditions like for the miners?

Working in the mines was very hard and the average age of death was only 45, compared to over 80 today. Boys as young as 10 would go down the mines to shift the rocks, often in dangerous working conditions.

The job of sorting through the crushed ore fell to women and children who sorted through for the best examples of galena. They worked long hours, earning only a shilling a day (the equivalent of about £3 today), plus two new woollen petticoats per year. Men earned about 2 shillings. For this sum, work was hard and labour-intensive.

Bukker from The Dales Countryside Museum

You can see two examples of the types of hammer used to remove lead from within larger pieces of materials extracted from the mine by smashing. One has a longer handle, but both tools were very heavy.

Watch The Video

Watch The Video With Subtitles

A range of other dangers

At the time, little was understood about the dangers of lead which, once crushed in the waterwheel, resulted in lead polluting the water. This water in turn ran downhill, polluting streams, rivers and farmlands and poisoning the people and animals who used the water.

Processing the ore also used a lot of materials including wood to heat and smelt the lead. In Kettlewell, they had to switch to burning peat and coal which also produce environmentally damaging chemicals.

Around the mine area, smoke and dust were so polluting that sometimes the mine owners had to pay compensation to farmers whose animals died as a result of poisoning. There are no records showing compensation for the the death of people!

Hired or Fired? Explore the story behind the waterwheel with your group. Could they have made it as lead workers?

Talking Points

When the volunteers were restoring the wheel one of the first jobs was to paint the ironwork. Why do you think this was important?

Waterwheels can be used for many jobs. How many can you think of? Are there any modern uses for waterwheels?

Waterwheels rely on plenty of water. This one used 680,000 litres per hour which is enough to fill 8500 baths! What happens if there isn’t enough rain?

If you visit Kettlewell today it is a quiet, peaceful place. How do you think it might have been different 150 years ago?

What would it have been like to stand beside the stone-crushing waterwheel whilst it was working? Do you think machinery like this would be allowed in a modern workplace?

There are two large stone weights hanging off the front of the rock crushers. What do you think they were for? Can you describe how they are acting as levers to multiply forces?

We don’t mine for ore in this way in Britain today. Instead we often rely on importing metals from other countries which have different child labour laws from ours. Would you buy a mobile phone if you knew a child had mined the metals used inside it?

Does the ‘bukker’ or hammer look like a tool that you would enjoy using? What would you find hard about working with it?

Why do you think there were different lengths of handle? Do you think you’d have found the short or the long handle easier to use?

Vocabulary

Mineral: a rock that contains particular chemicals

Ore: a rock that contains valuable materials like metals

Smelting: heating an ore to extract its metal, sometimes adding charcoal

Leat: a watercourse built to feed a waterwheel or mill

Potential energy: stored energy

Kinetic energy: movement energy

Power: how much work that can be done in a unit of time

Work: how much energy is transferred

Force: the push or pull on an object when you transfer energy to it

Bouse: the name given to raw material dug from a mine

In the Classroom

Debate

Imagine that a new, valuable mineral has been discovered in Kettlewell. A company wants to reopen the mines to extract the ore. In groups, discuss the advantages and disadvantages of reopening the mines.

Choose one person to hotseat and defend the plan to open the mines.

Interview them to find out if opening the mines is a good idea

Hands on History

You can see the Waterwheel from Providence Mine at the Dales Countryside Museum and find out more about local industries.

Museum Location

Find out more about working lives with these objects…